In a rapidly changing world, we need to know which areas of our planet warrant particular protection from existing, developing and forthcoming threats. This is hard to do objectively in the vast realm of the oceans, particularly so in the most remote regions such as the Southern Ocean. A paper published this week in the journal Nature (together with a companion data paper in the journal Scientific Data) describes a novel solution to this problem, using electronic and satellite tracking data from birds and marine mammals.

In a rapidly changing world, we need to know which areas of our planet warrant particular protection from existing, developing and forthcoming threats. This is hard to do objectively in the vast realm of the oceans, particularly so in the most remote regions such as the Southern Ocean. A paper published this week in the journal Nature (together with a companion data paper in the journal Scientific Data) describes a novel solution to this problem, using electronic and satellite tracking data from birds and marine mammals.

The solution relies on a simple principle: animals go to places where they find food. So, identifying areas of the Southern Ocean where predators most commonly go tells us where their prey can be found. For example, whales and penguins go to places where they can feed on krill, whereas seals and albatrosses go where they can find fish, squid, or other prey. If all these predators and their diverse prey are found in the same place then this area has both high diversity and abundance of species, indicating that this area is by definition of high ecological significance.

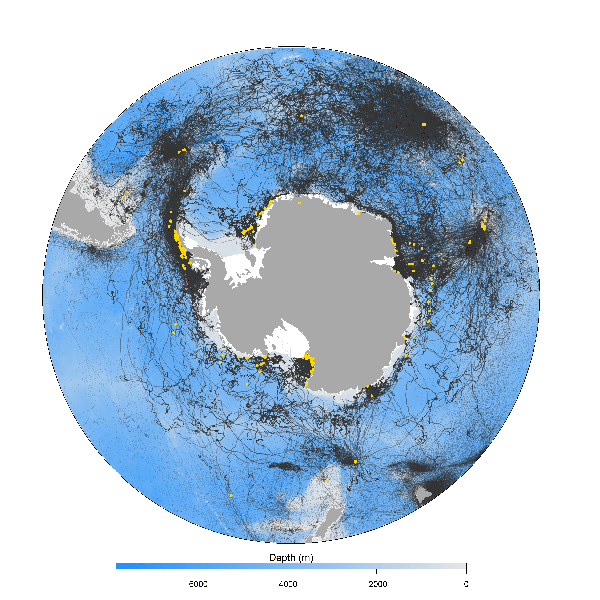

This community-wide initiative, termed the Retrospective Analysis of Antarctic Tracking Data, was a project of SCAR’s Expert Group on Birds and Marine Mammals. Support was received from the Centre de Synthèse et d’Analyse sur la Biodiversité, France, and WWF-UK. SCAR engaged its extensive network of Antarctic researchers to assemble existing Southern Ocean predator tracking data. After careful validation, the result was an enormous database of over 4000 individual animal tracks from 17 predator species with diverse prey requirements, collected by more than 70 scientists across 12 national Antarctic programs. This database is now available for public download.

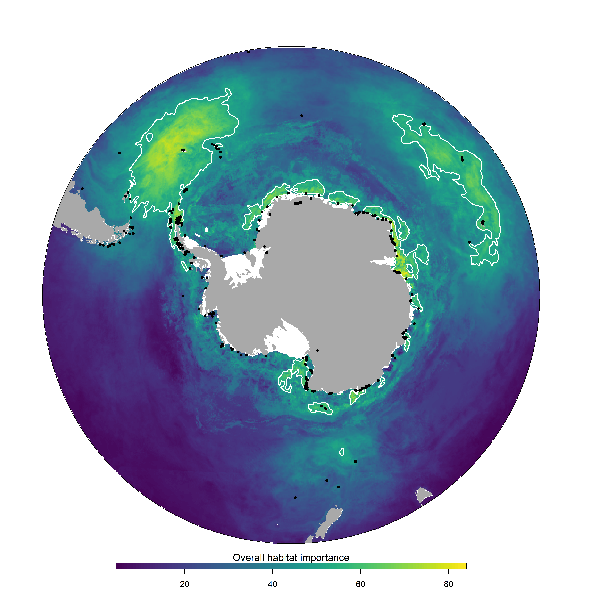

Even this impressive database does not directly represent all Southern Ocean predator activity, because it is impossible to track every species from all their breeding sites. Simple mapping would therefore provide a biased representation of animal distribution. To overcome this, sophisticated statistical models were used to predict the at-sea movements for all known colonies of each of the 17 predator species across the entire Southern Ocean. These predictions were combined across the 17 species to provide an integrated map of areas of ecological significance.

Even this impressive database does not directly represent all Southern Ocean predator activity, because it is impossible to track every species from all their breeding sites. Simple mapping would therefore provide a biased representation of animal distribution. To overcome this, sophisticated statistical models were used to predict the at-sea movements for all known colonies of each of the 17 predator species across the entire Southern Ocean. These predictions were combined across the 17 species to provide an integrated map of areas of ecological significance.

The most important of these areas are scattered around the Antarctic continental shelf and in two wider oceanic regions, one projecting from the Antarctic Peninsula engulfing the Scotia Arc and another surrounding the sub-Antarctic islands in the Indian sector of the Southern Ocean.

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are a crucial tool in the conservation management toolbox. Existing and proposed MPAs are mostly found within the areas of ecological significance, suggesting that they are currently in the right places. Yet, when climate model projections are used to account for how areas of important habitat may shift by 2100, the existing MPAs with their fixed boundaries may not remain aligned with important habitats in the future. Dynamic management of MPAs, updated over time in response to ongoing change, are therefore needed to ensure continued protection of Southern Ocean ecosystems and their resources in the face of growing resource demand by the current and future generations.