The following interview was conducted by Seira Duncan, who is a member of the Standing Committee on the Humanities and Social Sciences (SC-HASS). The interview was translated from Japanese to English.

Abstract: Despite their contributions, current academic and societal discourse pertaining to Japanese polar exploration shed little light on the Ainu who were part of the 1910-12 Japanese Antarctic Expedition. This article explores the lives and roles of two Ainu – Yasunosuke Yamanobe and Shinkichi Hanamori in the context of increasing calls in the academic community to document, as well as highlight, indigenous peoples’ roles in historical and contemporary polar research. Through the penning of Netsugen (2019), Souichi Kawagoe (re)introduces the two men’s contributions into mainstream Japanese consciousness. As such, this article reviews current research as a point of departure and proceeds to inform it via locally-acquired qualitative records in the form of two separate interviews.

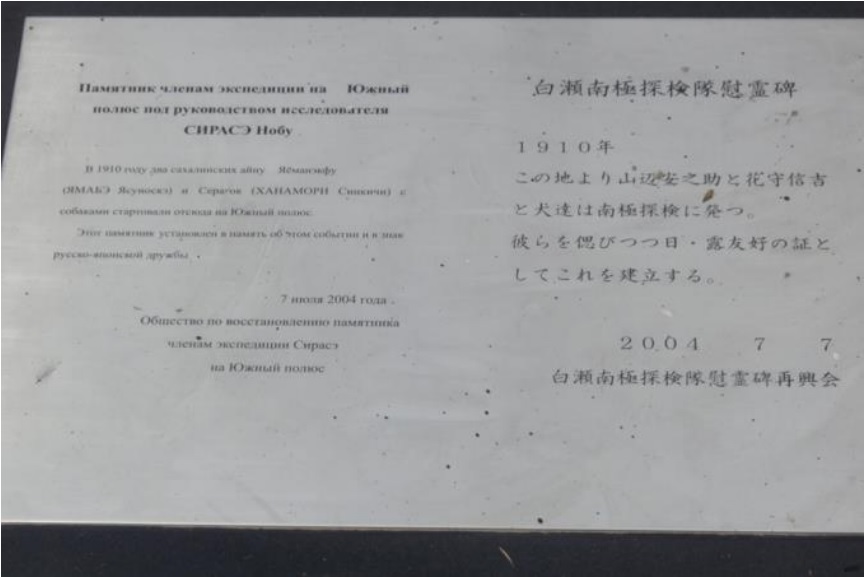

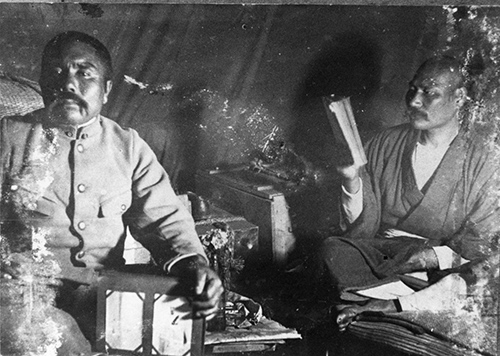

Northern Japanese prefectures (i.e. Hokkaido and nearby regions) are home to an indigenous group called the Ainu. Nobu Shirase, who led the 1910-12 Japanese Antarctic Expedition, was from Akita prefecture in northern Japan. Although not well-known by Japanese society, there were two Ainu men –Yasunosuke Yamanobe and Shinkichi Hanamori – aboard the ship. While the expedition was ‘quickly forgotten by the Japanese media and public’ the two Ainu men’s roles are starting to enjoy renewed interest due to the success of Souichi Kawagoe’s award-winning Netsugen (2019) (Morris-Suzuki & Iacobelli 2021). Yamanobe and Hanamori’s contributions show ‘striking parallels’ to those of the Saami on a Borchgrevnik-led expedition (Maddison 2020). Citing Maddison, Hofmyer & Lavery (2021) highlight the reality that narratives of Antarctic exploration are gradually becoming ‘indigenised’. A century after the Japanese Antarctic Expedition, Chuuetsu Sato wrote a book on Yamanobe and Hanamori’s time on Antarctica and Kawagoe, who won the Naoki Award (a prestigious literary award in Japan), referred to Sato’s publication as one of his sources. Sato and Yoshinori Hashida conducted research together on the Ainu through travelling to the islands and engaging with the locals. Hashida is also close friends with Yoko Abe, an Ainu woman he met at a port in Wakkanai, Hokkaido. Sato and Hashida kindly accepted my request to interview them on the Ainu, including the two men who took part in the expedition in the early 20th century. This article is thus situated in contemporary academic discourse on the role of indigenous peoples in polar exploration and aims to further contextualise such discussions through localising socio-cultural memories. The following are transcriptions of interviews with Hashida and Sato, respectively.

An interview with Yoshinori Hashida

The Sakhalin Ainu and Dr. Kyousuke Kindaichi

I read your articles and have a lot of questions. Please tell me about yourself and the connection between the Sakhalin Ainu and the polar regions.

I came to Akita from Kyushu and became interested in Yamabe – or Yamanobe – both are correct. There was a peculiar book called あいぬ物語 (Ainu monogatari) written by Kyousuke Kindaichi who had heard stories about Yamabe. Around 40% of the Sakhalin Ainu lost their lives to cholerae – the Sakhalin Ainu went through many adversaries. Yamabe was one of them. However, I was surprised by how little he was known despite his contributions. Most people who are older than 40 have read about the Sakhalin Ainu. Kindaichi’s essays 片 言を言うまで (Katakotowo iumade) and 心の小径 (Kokorono komichi) appeared in textbooks prior to the war. It outlines how Kindaichi learned Sakhalin Ainu from conversing with the children on the island. Although everyone has learned about the Sakhalin Ainu no one is interested in the subject – a gap that I found strange, and which led me to conduct interviews.

Contemporary Sakhalin and Yoko Abe

Concerning Abe – I was travelling to Sakhalin from Akita. I didn’t know anything at first but researched pre-war Sakhalin newspapers in the National Diet Library. Since around the turn of the millennium I visited Sakhalin several times and continued researching at a local museum. I worked alongside unofficial researchers. While travelling to and from Sakhalin I met Abe at a port in Wakkanai. It was her first time returning home since the war ended. Although she was initially quiet, we talked a lot and she told me that when she was moving to Japan, she thought to herself that she needed to write her story. We decided to write her autobiography together. Over the course of almost a decade she wrote her story and I transferred it to a word processor. Since the government was willing to fund the project, we published オホーツクの灯り (Okhotskuno akari). The title comes from a lighthouse close to her village which she mentions shed light on the Okhotsk Sea in her haiku. It was symbolic of the relation between their traditional lives and modernisation. She prefers to be seen as a human rather than a Sakhalin Ainu. She’s doing well and lives in the Kanto region now. I visit her around once every year.

Collaboration with Chuuetsu Sato and colleagues

It’s my understanding that you worked on Sato’s 南極に立った樺太アイヌ (Nankyokunitatta karahutoainu). Can you explain your relationship with him as well as the editorial process?

Seiichiro Watanabe at Akita Sakigake News wrote よみがえる白瀬中尉 (Yomigaeru Shirasechuui). It included a detailed account of the Antarctic Expedition. However, the more I researched, the clearer it was that it contained errors. Specifically, it writes that when Yamabe and Hanamori returned to Sakhalin after the expedition they abandoned their dogs and were taken to court. Watanabe heard it from an individual in the fishing industry who came to Japan from Sakhalin. However, the story doesn’t add up. I wanted to find out what really happened. At the Shirase Antarctic Expedition Memorial Museum in Akita, I met someone who wanted to change his then position and become a researcher for the museum – that was Chuuetsu Sato. We got along famously and did research together. Since あいぬ物語 (Ainu monogatari) there has been very little literature on Yamabe and Hanamori – you could say non-existent. Sato had no experience writing or publishing, so as an editor I gave feedback on his work. He went to Sakhalin and Hokkaido to conduct research. Initially, he published it with his own money. Someone at the Japan-Eurasia Society came across it and it became a book called Eurasia Booklet. However, the bookstore Toyo Shoten went bankrupt. 熱源 (Netsugen) by Souichi Kawagoe, which won the Naoki Award, has Yamabe as its protagonist. Kawagoe read 南極に立った樺太アイヌ (Nankyokunitatta karahutoainu) and included it in his references which made me wonder whether it was possible to have it republished, so I made a post on Twitter. Yoshitomo Narae is an artist interested in Antarctica and had read 南極に立った樺太アイヌ (Nankyokunitatta karahutoainu). He recommended a publisher called 青土社 (Seidosha) and it was republished in 2020.

An interview with Chuuetsu Sato

Please tell me about yourself and the connection between the Sakhalin Ainu and the polar regions.

I was born and raised in Konouramachi (modern-day Nikaho) and worked for 40 years. I wanted to give back to my town and thought about what I could do. It occurred to me that Shirase was from my town and realised the advantages connecting him to both Japan and other countries might have. Exactly a year ago the Shirase Antarctic Expedition Memorial Museum had been built and I became an employee. As I was researching, I learned that two Sakhalin Ainu – Yasunosuke Yamanobe and Shinkichi Hanamori – were part of Shirase’s team. We didn’t know who their descendants were and wanted to look into it. In 2000 there was an event which tried to start discourse pertaining to Shirase. With two others I went to Sakhalin – Hashida from Kyodo News and Watami from Akita Sakigake News. We wanted to identify Yamanobe and Hanamori’s descendants but didn’t get any leads. As I was researching, it made me realise the minority Sakhalin Ainu were thrown around by the flow of the times. I researched a lot about Yamanobe. He was an extremely high-minded individual and I was moved by his ardour for the Ainu. The Ainu were tricked and discriminated by the Japanese and Yamanobe said what would save the Ainu was education. As such, he built a school for the Ainu and participated in the Antarctic Expedition to change how the Ainu were seen.

Can you explain the relationship among the Japanese and the Ainu who visited Antarctica?

Initially the team wanted to take horses. The exploration ship ended up being smaller so they couldn’t take the horses. On short notice they decided to take Sakhalin dogs and the Ainu since they were used to handling them. Hashida mentioned there were disagreements between the Japanese and the Ainu. Nothing like that happened on the expedition. Having said that there was discrimination on Sakhalin and there were times when Yamanobe couldn’t accept how they were treated by the Japanese and had conflicts.

Please tell me about your relationship with Kawagoe.

Kawagoe wrote a novel called Netsugen which is close to non-fiction. My book was included in his references, and I felt honoured.

Can you tell me about the writing process?

I was moved by Yamanobe’s high-minded nature which was one of the reasons I wanted to write Nankyokunitatta karahutoainu. Additionally, as I was researching, I became very interested in the minority Sakhalin Ainu.

What do the Sakhalin Ainu think about the two who travelled to Antarctica?

To be honest, the community isn’t aware. As I said earlier, identifying as an Ainu leads to discrimination. People don’t share their Ainu identity. According to what I’ve heard, there was an individual who filed for a divorce after one of them found out the other was Ainu.

Did the two meet Amundsen? What would you say to people who are interested in polar regions and the Ainu?

No, they didn’t – only captain Shirase. I want people to know more about the Ainu who were thrown around by the flow of the times. It was one of the reasons I wrote Nankyokunitatta karahutoainu.

Discussion

As evidenced by Sato and Hashida’s responses, the two Ainu men’s roles in the early Japanese Antarctic Expedition have largely gone unsung. It is of paramount importance that indigenous minorities’ imprints in cultural heritage – past and present – are not only credited but celebrated, and it is clear that the quest to have traditionally muted voices heard is far from realised. Different minorities encounter different impediments; as Hashida highlights, the Saami experience in contemporary Nordic societies is not analogous to that of the Ainu in modern Japan. Abe’s insistence on being seen as another human rather than through an ethnic lens questions humanity’s ongoing preoccupation with differences rather than identifying commonalities.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude towards Chuuetsu Sato and Yoshinori Hashida for their time.

References

- Hashida, Y. (2021): Interview with Seira Duncan.

- Hashida, Y. (2021): Photographs.

- Shirase Antarctic Expedition Memorial Museum. (2021): Photographs.

- Hofmeyr, I. & Lavery, C. (2021): Reading in Antarctica. Wasafiri, 36(2).

- Kawagoe, Souichi. (2019): Netsugen.

- Bungeishunjuu. Maddison, B. (2020): Indigenising the Heroic Era of Antarctic exploration, in Leane, E. & McGee, J. (eds.) Anthropocene Antarctica: perspectives from the humanities, law and social sciences. Routledge.

- Morris-Suzuki, T. & Iacobelli, P. (2021): Japan search: introducing a new research tool for scholars of Japan and its region. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 19(1).